Sat, 30 August 2014

Finally, I thought this would be a fitting and poignant close to our tribute to Sonny Kamahele. I was in Hawai`i for my first attempt at the Aloha Festivals Falsetto Contest in July 2003. My wife and I were staying in Kane`ohe (after the lesson learned staying in Waikiki), but we also felt like we were missing out on the music scene down there. So, on Thursday evening, July 3rd – the night before the 4th of July – we ventured into Waikiki via the beautiful drive down the Pali Highway. But there were a number of celebrations taking place in town, and after being stopped cold in traffic well before the turn from Kamehameha Highway on to Pali Highway, this appeared to be yet another of our mistakes. We could not yet know that the two-and-a-half drive hour to town would be well worth it. (And sunset over the Pali Highway – in slow motion – would be worth it regardless.) As often happens at live music venues in Hawai`i – more than anywhere else I have ever frequented – musicians drop by to listen and pay respect to their musician friends. This particular evening at the Waikiki Beach Marriott was star-studded. But the highlight of the evening was a visit by Sonny Kamahele. Sonny assumed the rhythm guitar chair typically occupied by the venerable Momi Kahawaiola`a, and Alan (as you will hear on this recording) immediately says, “I guess you know what Aunty wants you to sing.” It was clear that this was not a first occurrence. After all, Aunty Genoa and Sonny were good friends who went way back in the Hawaiian music “biz” – appearing together live and on record (such as the long out of print Ka`alaea). You will then hear Aunty Genoa say, “I love that song, Sonny.” And then not wanting to push, she adds, “You sing what you want to sing. Don’t listen to me.” But Sonny obliges her anyway and launches into a 1938 French classic, “J’Attendrai,” which means “I Will Wait.” (It is not, in fact, a French song but was actually translated from the original Italian tune “Tornerai,” which means “You Will Return.”) Announcing Sonny, Alan speaks of the origins of the song but adds, “And then he makes it more Hawaiian. You’ll see how.” Sonny accomplishes this by singing the French tune largely in his gorgeous Hawaiian falsetto. And, as expected, the audience goes absolutely nuts. After Sonny’s peppy take on “Na Moku `Eha” (a lyric with as many as five different melodies – perhaps more), the group surprises us yet again by calling to the stage more Hawaiian music royalty – Sonny’s sisters, Iwalani Kamahele Stone and Anita Roberts. Although she made scant few solo recordings (most appearing on 45 rpm singles or on compilation LPs from the Waikiki Records label in the early 1960s), Iwalani ‘s unmistakable soaring soprano graced many a recording by such artists as Charles Kaipo Miller and Chick Floyd. She was also a member of the Hawaii Calls orchestra and chorus and performed on their weekly radio shows and on their Capitol Records LPs. You would recognize Iwalani’s voice instantly even if it were not identified in the liner notes (which, as was often the case with Hawaiian music LPs, it wasn’t) because her voice could easily be mistaken for a piccolo. The sisters open their much too short set with a duet of Charles E. King’s “Lei Aloha, Lei Makamae” in which you hear Anita’s lovely contralto singing (what is typically) the male part of the duet and Iwalani’s soprano taking the female part. (Listen as Iwalani effortlessly reaches “G” above “high C” in the choruses.) Iwalani then solos on Lena Machado’s “Kaulana O Hilo Hanakahi” before sister Anita closes the set with the long forgotten “Here In This Enchanted Place.” All the while the sisters are accompanied by their brother, Sonny, on guitar, Alan Akaka on steel guitar, Gary Aiko on bass, and Aunty Genoa on the `ukulele who you might hear cheering them on the whole time as if this entire display were for solely for her. Because, frankly, it was! As the clip fades, listen to Alan, Gary, and Aunty Genoa heap praise on the combined talents of the Kamahele `ohana. There is nothing more heartwarming for a musician to experience. Musicians regaling musicians is the order of the day in Hawai`i, but even in this regard this particular evening was truly special. It was also one of the last I spent with Sonny before his passing in February 2004. I heard him twice more at the House Without A Key that July, but by the time I returned to Hawai`i in September, Sonny had already retired from the Halekulani Hotel the month before and moved to his new home on Hawai`i island. I would never see him again. But I cherish the moments I had with him. I hope you enjoyed this tribute to my hero, Sonny Kamahele, and especially this last segment captured exactly as it happened at the Waikiki Beach Marriott on the evening of July 3, 2003.

Direct download: Sonny_Kamahele_with_Genoa_Keawe_-_7-3-03.mp3

Category:Artists/Personalities -- posted at: 4:53am EDT |

Fri, 29 August 2014

In discussing Sonny Kamahele, you have already read that he spent the last 20 years of his career with a group known as The Islanders. While the membership often rotated – as Hawaiian music groups have done throughout the ages – depending on who is available for the gig that evening, The Islanders were anchored by their leader, virtuoso steel guitarist Alan Akaka. Other members at various points included such Hawaiian music stalwarts as Harold Haku`ole, Walter Mo`okini, Merle Kekuku, and Benny Kalama. But Sonny was pretty much always there in the all important rhythm guitar chair. The group requires no further discussion really than the name dropping for these are the guys who preserved – for as long as they could and for as long as the Waikiki tourist trade would allow them – old school Hawaiian music. When you hear The Islanders, you are hearing faithfully recreated the sound of the swinging Hawaiian music aggregations of the 1940s through the 1960s – sounds reminiscent of the Royal Hawaiian Serenaders (led by Alvin Kaleolani Isaacs, who we will also celebrate this week) and the Hawaiian Village Serenaders (of which Sonny and Benny were both members). Except for that which was captured by tourists, there is little extant video of those halcyon evenings at the House Without A Key. But a popular local TV series of the 1990s – Island Music, Island Hearts – brought the best combination of The Islanders into the studio to tape a few numbers for a most appreciative audience. (The episode paired segments featuring the very traditional sounds of The Islanders with the more contemporary sound of Brother Noland and Tony Conjugacion who were riding high on a pair of early 90s CDs that were pretty revolutionary in inching Hawaiian music into the 21st century – Ku and Ku2. Their segment is worth seeking out on YouTube. And because the original YouTube video poster – who deserves credit for preserving these precious moments in Hawaiian music history – did not have the courtesy to credit the musicians involved by naming them, finding either of these videos would likely prove challenging without a little assistance. But I digress…) In this all too brief clip – the entirety of their appearance – Sonny, Alan, and Benny give their all on a medley of songs which island hop from Kaua`i to Maui. They open with “Hanohano Hanalei,” Alfred Alohikea’s composition extolling the beauty and virtue of the Garden Isle. We should be forever grateful to Island Music, Island Hearts for capturing so many legends of Hawaiian music in their prime in only two dozen episodes. As a gift many years ago, my father compiled nearly every episode of this groundbreaking show on one VHS tape (you remember those, don’t you?), but this clip of The Islanders is the one I truly cherished. I hope you cherish it too.

Direct download: Island_Music_Island_Hearts_-_The_Islanders.mp4

Category:Artists/Personalities -- posted at: 5:55am EDT |

Thu, 28 August 2014

I had always loved Hawaiian music. And so I loved the idea of Hawai`i despite that I had never been there. I had only learned about Hawai`i through books, magazines, television and movies, and – of course – the music. So when I landed at Honolulu International Airport on October 2, 2000 – my thirtieth birthday – I had a few destinations in mind as soon as I threw my bags in my hotel room at a 1-star hotel (my first mistake) in Waikiki (my second mistake). My then wife – tired from the nearly 11-hour flight – simply wanted to crash. But who knew if I would ever get back to Hawai`i? But this was not only my birthday; it was also the first day of our honeymoon. So we engaged in our first marital dispute. I was going out – with or without her. I did not come to Hawai`i to sleep. And I told my wife that if she came along, she was in for a treat and that it was only a four-block walk away. And with that, I officially won our first argument, and we set out for the Halekulani Hotel. The short walk led to the paradise I had read and heard about. A quintessential “must see” for the first time Hawai`i tourist is sunset at the Halekulani’s “House Without A Key” (so named for the first Charlie Chan novel written by Earl Derr Biggers, a 1925 first edition copy of which sits on the end table beside me as I write this). But it is not merely the sunset. It’s the view of Diamond Head just beyond your view of the Royal Hawaiian and Moana Hotels – a Waikiki the way it used to be. It is the Halekulani Iced Tea complete with generous sliver of sugar cane to be used as a stirrer. It is the sheer elegance and the service to match. It is the hundreds of years old kiawe tree under which resides the barely raised bandstand. And it is the musicians who grace the bandstand seven nights a week – Hawai`i’s finest – and the stalwarts of the hula who join them, such legends as Debbie Nakanelua Richards and Kanoe Miller both of whose grace are unparalleled and beauty timeless in a way that redefines the word “timeless.” On this particular evening – as I knew would be the case from reading Hawai`i Magazine and the Honolulu Star-Bulletin – I knew I would find The Islanders – Alan Akaka, Kaipo Asing, and Sonny Kamahele. And it is now – as it has always been – the music that makes the House Without A Key a uniquely Hawaiian experience worthy of Frommers. This was the first of many evenings at sunset spent at (what the local musicians affectionately refer to as) HWAK. And was it ever memorable. I had known Alan – at least virtually, which in that era meant by mail with paper, stamps, the works – since 1994. But I finally got to meet my friend in the flesh – a friendship that has endured now for 20 years. But it was meeting Sonny that completely blew me away. We chatted between sets and then again for more than two hours after the final number. My then new wife was probably livid with me as 10:30pm HST would have been 3:30am EDT, by which time we were already up for more than 24 hours. But I was living the dream, and I wondered if such a night could ever happen again. (It would, but I did not have the prescience to believe that it could.) Sonny regaled me with stories about the musicians I admired but who left us long before I had ever arrived in Hawai`i – Lena Machado, Haunani Kahalewai, Alfred Apaka, Barney Isaacs, Jules Ah See, and, of course, his good friend (and verbal sparring partner) Benny Kalama. And we sang together, of course. That is what musicians do when they get together – formally or informally. But I never thought that could happen to me. (The clip you are listening to right now is from that evening. I would respectfully ask that we defer any debate about how such an illicit recording came into my possession or the ethics around whether or not it should be shared. I would retort by directing you to YouTube where such illicitly made recordings now number in the tens of millions. If you do not understand and subscribe to Ho`olohe Hou’s mission by now, then let me begin again. I aim to preserve the music and artists of Hawai`i that might otherwise be forgotten. And sometimes this might mean rolling out something from my vast archives that was not commercially released. In this case, there is no other way to experience an evening at the Halekulani – if you have never made it there in the flesh – than a recording such as this. While there will be those who will be angry at me for taking, keeping, and sharing recordings that were not commercially released, there will hopefully be many more who will be grateful for these archival efforts.) And here is just a snippet of what we heard that lovely evening in 2000… Sonny opens the first medley with the staple “Henehene Kou Aka (For You and I).” Notice that when Sonny sings the solo choruses, he is singing in his usual full baritone, but on the repeat choruses where everybody chimes in on vocals, Sonny jumps an octave to sing the lead in his lovely falsetto. Kaipo then takes the lead vocal on “Hanohano Hawai`i” during which Alan takes a chord melody solo on the steel which prompts me again – for the second time today – to state emphatically how much like Jake Keli`ikoa he can tend to play at times, a sound that much deserves to be perpetuated, and it is in the capable hands of kumu Alan. He also closes the medley by singing one of his favorites, “I’m Going To Maui Tomorrow,” a novelty number written surprisingly by comedian Bill Dana (who created the persona of José Jiménez) who once had a stage show in Waikiki. The next medley again features Sonny’s falsetto – first on the Alvin Kaleolani Isaacs chestnut “Aloha Nui Ku`uipo,” and then on the hapa-haole classic “For You A Lei.” Performances at the Halekulani can be very fluid – comprised of long medleys, largely unplanned, just singing songs as they pop into the heads of the singers, everyone on stage taking a turn, constantly changing keys… During this medley, you hear Alan suggest that Sonny sing “For You A Lei” as he witnesses a uniquely Hawaiian moment – the giving of a lei. And as can only happen in Hawai`i – which I now understand is the center of the universe, not merely the crossroads of the Pacific – the giver of the lei was none other than Ben Chapman of Creature From The Black Lagoon fame. The set closes with still another medley. The group does a number sometimes entitled “Hoe Hoe” (or “Sam Koki’s “Hukilau”), followed by Alan singing another Alvin Isaacs song, “E Mau” (which speaks of the importance of perpetuating Hawaiian things), and finally one of Andy Cummings’ many swingers, “Tropical Swing.” Listen to Sonny’s rhythm guitar work and his high harmony in falsetto in this last medley – recreating the critically important role he played with both the Hawaiian Village Serenaders and the Hawaii Calls orchestra and chorus. I hope you enjoy this music that might otherwise have been lost, and I hope you enjoyed another glimpse into the life and career of Sonny Kamahele who – as you can hear – was amazing to the very end. |

Thu, 28 August 2014

Google “Sonny Kamahele” and the first search result is indeed an oddity. In an entry on “The Best Luxury Hotels on Oahu,” the online version of Frommers travel guide is quick to point out that although most cannot afford to stay at the “money is no object” Halekulani Hotel, one must still drop by some evening at sunset and sip a mai tai at the House Without A Key while Sonny Kamahele serenades them. Uncle Sonny left us more than 10 years ago now. This Frommers entry then either speaks to the editors’ inattentiveness or the seeming invincibility of the gentleman with arguably the longest career in Hawaiian music show business. Who ever thought the immortal Sonny Kamahele could ever die? Certainly not me. Solomon “Sonny” Kamahele was born August 28, 1921 in Honolulu, Hawai`i. I don’t even know how to describe adequately the career of someone who – in a more than 60 year career as a singer, multi-instrumentalist, bandleader, and arranger – literally and figuratively “did it all.” Sonny’s was no doubt one of the most illustrious careers in the history of Hawaiian music. But a few highlights… Sonny broke into show biz at the age of 19 with his father’s orchestra performing at the two hottest, swingingest night spots in Waikiki of the 1930s and 40s – the Moana Surfrider and the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. By 1948 he headed off to perform at Hollywood’s purveyor of Hawaiian culture, the now famous Seven Seas Supper Club, in a show led by Sam Koki. During this same period, Sonny was doing studio and TV work, performing in the Harry Owens’ Orchestra for his then popular TV show which was naturally produced in Hollywood. Sonny stayed on the mainland nearly a decade, but by 1956 he returned to his home in Hawai`i where one with his immense talents would no doubt immediately find work with a group that would become legendary not only for its all-star members, but also for the company it kept. Benny Kalama enlisted Sonny for a group he was leading called the Hawaiian Village Serenaders, so named for the Hawaiian Village Hotel where the group was performing sometimes twice nightly backing legends of Hawaiian entertainment such as Alfred Apaka and Hilo Hattie. Throughout the 1960s Sonny led his own group at this same hotel’s Surf Room. And at the same time as all of these other 60s engagements, Sonny was also an in demand studio musician who appeared on more recordings than one can count (often uncredited except to those who recognize his guitar playing or his voice), and he was a critically important member of the Hawaii Calls radio program’s orchestra and chorus – lending his guitar and voice for both the radio and (short lived) TV versions of the program as well as on innumerable recordings which found their way around the world courtesy of the shameless promotion of Capitol Records. And, oh, that voice! Sonny’s gorgeous pipes ranged from the highest, sweetest falsetto you have ever heard down to his lowest basso profundo which he used to great effect on the Hawaii Calls novelty numbers. And he was the last of a rare breed of rhythm guitarists who played in the real old style – part guitarist, part drummer, heavy on the syncopation, an upstroke as well as a downstroke with the pick. (Today’s Hawaiian rhythm guitarists do not value the upstroke highly enough, I fear.) And many may have already forgotten that Sonny was handy with a steel guitar, as well – mastering the seldom used D9th tuning. I knew Sonny personally from the final period of his career which he spent at the Halekulani Hotel’s famed House Without A Key. I used to go listen to him play with The Islanders, a group led by steel guitarist Alan Akaka, at the venue local musicians once referred to affectionately as “HWAK” where they performed for nearly 20 years from September 1983 until Sonny’s retirement in August 2003. We lost Sonny much too soon in February 2004. He was only 82 years old. Like Frommers, I thought Sonny would live forever. But do the math. He passed away less than six months after retiring. He and his wife had just built a house on the Big Island. He never had an opportunity to enjoy it. He gave the best years of his life to the music. Sonny left us a legacy of hundreds of recordings. You would be hard pressed to find the best of these in the digital era. Only his final few solo albums were released in CD format. Sonny’s recorded work as a leader in the 1960s remains out of print, as do the many recordings with the Hawaiian Village Serenaders. And on others still Sonny languished in obscurity as the liner notes of the recordings on which he fulfilled that one-time studio need – on guitar, `ukulele, or bass – rarely credited the sidemen if they were not part of the featured artist’s regular working group. Because Sonny could do everything, I wanted to feature some recordings that showcase the best of everything Sonny was and continues to be the epitome of to so many of us. You will hear a little of everything Sonny did here – his rhythm guitar, his steel guitar, and – especially – the voice in all of its incarnations.

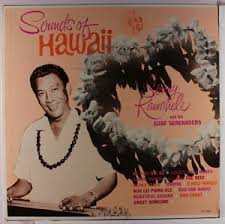

“Ku`u One Hanau” was written by Sonny’s father, Sol Kamahele Sr. The ironically titled 1960s LP release, Sounds of Hawaii was one of the first on the then burgeoning Sounds of Hawaii label. And you hear Sonny’s lilting falsetto on this selection. This album remains out of print. The Alfred Alohikea composition “Ka Ua Loku” is from another Sounds of Hawaii release, Say A Sweet Aloha which also remains out of print. “Ta-ha-ua-la,” an Alvin Kaleolani Isaacs composition, is from the first release by Alan Akaka and The Islanders, How D’Ya Do. The recording largely featured the same working group that was appearing nightly at the Halekulani Hotel during this period. Modeled on supergroups like the Hawaiian Village Serenaders, The Islanders could be a different group on any given night but would always feature elder statesmen of Hawaiian music like Benny Kalama, Walter Mo`okini, Harold Haku`ole, Merle Kekuku, and – of course – Sonny. The youngest lions among the group were Kaipo Asing and the leader, Alan Akaka. But Alan was immediately accepted by the legends as he was one of a handful of young men in this time period (the late 1970s/early 1980s) who had not only taken up the steel guitar, but who chose to play it in the real old style. Despite being taught by the man who is arguably considered the master of the instrument, Jerry Byrd, Alan’s style is more reminiscent of the jazzy steelers of the 1940s and 50s. When I listen to Alan, I hear echoes of Tommy Castro, Steppy de Rego, Jake Keli`ikoa, and Jules Ah See. It has been many years since this recording was made, and Alan is now a legend himself. It was inevitable.

Gary Aiko’s golden baritone takes the lead on the next number which was arranged by Sonny for the Hawaiian Revue at the Coconut Grove Night Club, a revue (photo below) which recreated the sights and sounds of Hawaiian music in the 1920s and 30s – an experience Sonny was uniquely qualified to reproduce since he had been a part of that era, playing in the larger dance bands that would have been featured at the Moana and Royal Hawaiian Hotel as well as in the orchestra led by Harry Owens. Sonny created such arrangements as you hear here in the style of that era. I chose to spin “The Cockeyed Mayor of Kaunakakai,” which we can imagine in performance was accompanied by a comic hula. “Halekulani” – one of Sonny’s last recordings – is a testament to Sonny’s various abilities since he not only wrote the song for his musical home at the Halekulani Hotel, but he also performed all of the instruments you hear except the bass (which was handled by his stepson, King Kamahele). This means that is Sonny’s beautiful steel guitar work you are hearing. Taken from the same CD as “Halekulani,” the 1996 release Beautiful Hawai`i, Sonny accompanies himself again on steel guitar (in that D9th tuning) on “Sleep Little Baby” which was composed by Sonny’s musical partner in Hollywood, Sam Koki, who wrote the song for his son. It is a fitting tribute to Sonny as it was the last song he ever heard. Amy Hanaiali`i sang it to Sonny over the phone in the minutes just before he passed away. I miss Sonny in as many ways as he had talents. I not only miss his music, I miss his spirit and his kolohe nature. Unlike some of the other relationships I have had the privilege of forging with Hawaiian music legends, it would be disingenuous of me to call Sonny my “friend.” We didn’t know each other well enough. But we shared many a lovely evening after his performances at HWAK, sitting under the kiawe tree hours after the gig ended until Halekulani staff ultimately had to kick us out or sweep around us. He regaled me with stories of a Hawai`i – and a Hawaiian music scene – that I will never knew. Sonny was my hero, but he also personally knew so many of my other heroes that he was my “one degree of separation.” Despite being a legend, Sonny was a most unassuming presence – dressing to the nines in the all-white uniform he himself conceived of for the Halekulani gig (and which the bands which came after still wear to this day), but playing a vintage Gibson archtop so ravaged by time that it was held together with duct tape. And that pretty much sums up the Sonny I will always remember. - Bill Wynne |

Wed, 27 August 2014

Rarely do you hear or read a tribute to a bass player in a Hawaiian band. In the jazz world, if a Ray Brown, Slam Stewart, or Percy Heath passes away, tributes abound for each of those gentleman is known – in his own way – as breaking new ground in the art of the jazz bass. But in Hawaiian music, not so much. But if jazz bassists are constantly trying to break new ground, in Hawaiian music the bass is the ground itself. Except at certain junctures in the story arc of Hawaiian music history, rarely is there a drummer in a traditional Hawaiian band. The core of the Hawaiian rhythm section is often a combination of guitar and bass, `ukulele and bass, or guitar-`ukulele-bass. Notice what all of these have in common? The bass. |

Mon, 25 August 2014

|

Mon, 25 August 2014

If you haven’t already done so, don’t forget to like Ho`olohe Hou on Facebook. When you do, you might also check the box to “Get Notifications.” If you do, Facebook will never let you miss a new post, AND you will never miss out on contests like the one that begins later today. Check us out on Facebook today!

Category:Announcements

-- posted at: 12:17am EDT

|

Fri, 22 August 2014

When writing about James Ka`upena Wong yesterday, I promised myself that – despite that Wong is among the great living practitioners of Hawaiian chant – I would not write about chant because I know too little about it to be informative to the reader. At the same time, since my last post I have been listening to the few extant recordings of Wong’s chants over and over again, and I realize that this art form – in the hands and mouth of a master – is so compelling that it transcends language. Which is no doubt why Wong has been chosen time and again to represent Hawai`i and this art form across the nation and around the world. So, contradicting myself (not the first time I have done so, and certainly it won’t be the last), I want to share with you here two short pieces of chant performed by Wong – especially for those unindoctrinated in the art form. The two pieces are somewhat different in form – providing a launching pad for an on-going discussion on Hawaiian chant. For this reason, I offer up these pieces in reverse chronological order of that in which they were performed and recorded. And I will rely upon some experts along the way to give these chants and differing chant styles the appropriate context. For more than 25 years, one of my most invaluable resources has been Nathaniel B. Emerson’s Unwritten Literature of Hawaii. (I first located this volume in 1989 at the Bucknell University library, already long out of print. Fortunately it is back in print and – because of its age and entry into the public domain – is also available electronically free of charge courtesy of Project Gutenberg.) Emerson describes oli as follows: In its most familiar form the Hawaiians--many of whom possessed the gift of improvisation in a remarkable degree--used the oli not only for the songful expression of joy and affection, but as the vehicle of humorous or sarcastic narrative in the entertainment of their comrades. The traveler, as he trudged along under his swaying burden, or as he rested by the wayside, would solace himself and his companions with a pensive improvisation in the form of an oli. Or, sitting about the camp-fire of an evening, without the consolation of the social pipe or bowl, the people of the olden time would keep warm the fire of good-fellowship and cheer by the sing-song chanting of the oli, in which the extemporaneous bard recounted the events of the day and won the laughter and applause of his audience by witty, oft times exaggerated, allusions to many a humorous incident that had marked the journey. If a traveler, not knowing the language of the country, noticed his Hawaiian guide and baggage-carriers indulging in mirth while listening to an oli by one of their number, he would probably be right in suspecting himself to be the innocent butt of their merriment. The lover poured into the ears of his mistress his gentle fancies: the mother stilled her child with some bizarre allegory as she rocked it in her arms; the bard favored by royalty--the poet laureate--amused the idle moments of his chief with some witty improvisation; the alii himself, gifted with the poetic fire, would air his humor or his didactic comments in rhythmic shape--all in the form of the oli. Simply put, before the introduction of a formal system of writing, the Hawaiians depended on the oli as the primary medium for preserving oral histories and traditions such as genealogy, special places, important events, and prayers. With regard to the oli style, Jonah La‘akapu Lenchanko writes at Kūlia I Ka Nu`u (the Kamehameha Schools webs resource for Hawaiian language and cultural competencies): The beauty of the world of oli is that it is a very individualized effort. Each chanter has his or her own different voice quality and technique. Even the way a chant is chanted can differ depending on each individual’s past training and genealogy in chanting. It is said that chanting is a very "lonely" art. It is usually done as a solo performance by a chanter without any kōkua (help) from others. As such, the performance of an oli may sometimes be done differently by the chanter at each occasion. In the section on “Chant” written for the original edition of Hawaiian Music and Musicians, ethnomusicologist Elizabeth Tatar formally describes some of the essential elements of oli: - The oli is typically performed by a soloist without any instrumental or percussive accompaniment. - The range of pitches is small (on average, a minor third, a major second, or a fourth). - The number of different pitches that can be distinctly heard are few (perhaps two or three). - Rhythmically the oli lacks a regular pulse and meter. There are other features of the oli, but it is this last that those new to the art form will immediately recognize distinguish the style. There is melody but not a defined meter, and so oli straddles a line between speech and song. You can hear this feature in this selection from the 1970s National Geographic compilation album The Music of Hawaii (no longer available). Rather than create a compilation LP of previously released material, National Geographic funded an entirely new recording by artists carefully selected to represent the finest in “Hawaiian folk music.” For the occasion, Ka`upena Wong was chosen to record an emotional oli entitled “Eia Hawai`i” which speaks of the arrival in Hawai`i of the Polynesian voyagers who had sailed for weeks across a previously uncharted Pacific Ocean from their home in Tahiti. The oli begins… Here is Hawai`i, an island, a man Hawai`i is a man A man is Hawai`i A child of Tahiti Contrasting with the mele oli¸ the second selection is a mele hula. It differs from the oli in a number of ways that again will be immediately recognizable to the listener, but the most important features which contrast the mele hula from the oli are: - The mele hula is intended for the hula and, therefore, typically has (at least) rhythmic accompaniment such as the pahu (drum) or ipu heke (gourd). - Because it is intended for the hula, the mele hula will typically have a regular pulse and meter. Just as there are many types of mele oli, there are indeed many types of mele hula. The one heard here is a mele ma`i, genital or procreative chants which – according to Kihei de Silva – “were traditionally composed at the birth of a child -- especially the first born -- in order to celebrate and encourage the perpetuation of that child’s family line.” Ka`upena Wong here performs “Talala A Hipa,” or “The Bleat of the Ram,” which describes the rambunctious behavior of a ram – a reference to the subject of the mele, Kamehameha V. This recording was made in performance at Punahou School in 1964 shortly before Wong left to perform at the Newport Folk Festival. Taken from a long out of print LP, the Hawaiian music world should be grateful for the efforts of ethnomusicologist and kumu hula Dr. Amy Ku`uleialoha Stillman who – with the assistance of Michael Cord and Hana Ola Records – compiled this and nearly two dozen other forgotten chant recordings into digital form for the 2010 release Ancient Hula Hawaiian Style – Volume I: Hula Kuahu. The selections are translated and annotated by Stillman with her usual meticulous attention to detail – making this an invaluable entry in any Hawaiian music collection and an excellent primer for those previously unindoctrinated in the art of chant until reading this blog. There is still one more entire volume of chant by Ka`upena Wong – the 1974 LP Mele Inoa – Authentic Hawaiian Chants, which has not yet been made available in digital form. This is a pity since – as you have now heard – Wong is the master of the art form of chant and – as Stillman so succinctly states – “undisputedly the most renowned chanter of his generation.” |

Thu, 21 August 2014

James Ka`upena Wong is a lifelong student of all things Hawaiian. Born August 21, 1929 into a family rooted in Hawaiian culture – his mother was an accomplished hula dancer and his father was a singer – Wong is considered a leading consultant in Hawaiian language but – more specifically – in the once dying art form of chant. Upon returning from college in 1959, Wong began a 12-year apprenticeship with the foremost Hawaiian cultural expert, Mary Kawena Puku`i through which he learned the Hawaiian language, of course, and used it in the service of becoming a master chanter. (Chant was a primary form of language transmission before it was being actively taught in primary schools in Hawai`i.) More than this, he is also one of the few masters of the ancient instruments – such as the pahu (drum) and the 'ukeke (musical bow) – used to accompany the chant. Along with Professor Barbara Smith, Wong helped establish a program in Hawaiian chant and hula at the University of Hawai`i, the first representation of Hawaiian culture in higher education in the state. Wong has received countless honors throughout his lifetime. But perhaps most notable is that he and his friend, fellow musician and cultural expert Noelani Mahoe, were invited by Pete Seeger to perform at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964. (According to the National Endowment of the Arts, which granted Wong the “National Heritage Fellowship” in 2005 for his contribution to and perpetuation of Hawaiian culture, this performance at Newport is generally acknowledged as the first presentation of Hawaiian chant as an American folk tradition.) In yet another groundbreaking – literally and figuratively – moment, in 1969 Wong performed for the dedication of the statue of King Kamehameha I in the rotunda of Statuary Hall at the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. Because I am not a practitioner of chant, it is Wong’s skills as haku mele (composer) which are of primary interest to this discussion. Although not nearly as prolific as his kumu (teacher/mentor) Kawena Puku`i, Wong’s compositions continue to be cherished and sung to this day – even if the singers may have no idea he composed them. I thought I would share a few of my favorites with you. One of his first compositions, “Alika Spoehr Hula” honors Alex Spoehr on the occasion of leaving his tenure as director of the Bishop Museum. (This is a time-honored Hawaiian tradition of writing songs in honor of people – the result being known as a mele inoa, or “name song.”) This honoring song is sung here by the rare pairing of Marlene Sai backed by Buddy Fo and The Invitations. I count among my favorite love songs of all time Ka`upena’s composition “I Whisper Gently To You,” performed here by his longtime friend and musical partner, Noelani Mahoe. This recording is notable as being one of the last – and few – recordings of my dear friend Harold Haku`ole on the steel guitar. Finally, falsetto favorite Keao Costa sings “Ku’u Lei Pikake.” Although it seems not all that long ago, many of us have already forgotten that before his tenure with Na Palapalai, Keao was a solo artist with a beautiful and successful CD entitled “Whee-Ha!” This beautiful CD is regrettably no longer available, but it gives me great honor to spin it for you again and to honor my friend, Keao. Ka`upena Wong continues to contribute to Hawai`i and its people to this day as a teacher and mentor. |

Tue, 19 August 2014

August 19th marked the seventh anniversary of the birth of Ho`olohe Hou. But Ho`olohe Hou has had so many starts and stops that I should be very clear what this is the anniversary of. Ho`olohe Hou had an inauspicious beginning as a podcast on January 1, 2006. But it was short lived. After only six episodes – critically acclaimed by Hawai`i’s musicians and distributed widely across the Hawaiian music blogs, chat rooms, and threaded discussion boards – I was advised to “shut it down” to protect myself. At the time, there was no legal means of using copyrighted music in podcasts – an issue eventually escalated all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. But despite that I did not generate any revenue from my podcasting revenue, I could have been fined heftily – or even imprisoned – for spinning Hawaiian music recordings – despite that the recordings I played were largely out of print for 40 or more years, despite that most of the artists and composers had long ago departed this life. Fearing reprisal or legal action, I gave up. Enter a Hawaiian music lover with an entrepreneurial spirit, Don Narup. Don spent his life in high finance, but his passion was Hawaiian music. Upon his retirement, Don decided to use some of his investment acumen to fund one of the early internet Hawaiian music radio stations from his home in Las Vegas. And thus 50th State Radio was born. Don heard about my podcast and its too soon demise. He reached out to me, and we struck a partnership. Despite that he could not pay me to produce my show as the station was in its infancy, he could pay to produce it legally and ethically. Unlike podcasts at the time, the royalty rates for radio stations were long ago firmly established. Don took on Ho`olohe Hou, giving me a 9:30am Sunday time slot – immediately following a Christian chat program hosted by Reverend Gary Haleamau and his wife, Sheldeen. And what was once a humble podcast became a weekly two-hour radio program which – through 50th State Radio – reached listeners around the world via the internet. And because the world included Hawai`i, Narup eventually agreed to move the show to a 6pm Sunday evening timeslot to accommodate the many fans across the Pacific. But this, too, was short lived. One week in April 2008, I uploaded my program via FTP to 50th State Radio’s servers, and I waited eagerly at 6pm to hear my own voice hit the airwaves – fancying myself a Hawaiian-style Ryan Seacrest, opening each program with, “It’s time for more music and memories of Hawai`i. THIS is Ho`olohe Hou. Are you listening?” But the show never aired. The station appeared to be on autopilot – songs streaming, but no voice-overs, no time checks… I started calling the station. No answer. I started calling Don’s cell phone over and over again frantically. No answer. No response came until two days later when I received a call from Don’s wife with whom I had never spoken previously. I was shocked to learn that Don was dead – throat cancer, about which he clearly knew but chose not to treat, and about which he told nobody, and certainly not the staff at the station. 50th State Radio was Don’s dying wish, but sadly, the wish died with him. There was no further funding source beyond his passing. And, so, with Don’s passing, so, too, passed Ho`olohe Hou into oblivion yet again. Over the years – with the help of friends who also happen to be ardent Hawaiian music lovers – I have tried to breathe new life into Ho`olohe Hou the radio program. But to no avail. There is too little market for Hawaiian music, and that market is already flooded with awesome broadcasters, and what the hell could a haole guy from New Jersey know about Hawaiian music anyway? But the truth is that my show is different from Territorial Airwaves and others. Arguably, my collection of more than 25,000 Hawaiian music recordings is one of the largest in the world, and I have access to recordings that even Harry B. Soria does not – unofficial and unreleased recordings given to me by the artists themselves or their children and grandchildren. They were given to me because they knew I would know what to do with them – preserve them and share them, ensure that these Hawaiian music legacies endured. But I have not been given the opportunity again since 50th State Radio. Moreover, my approach to sharing this music may be different from other broadcasters. My life has been what ethnographic researchers might refer to as a “practitioner inquiry” – or learning by doing. I am not merely a Hawaiian music fan. I am also a musician practicing as much of the Hawaiian music craft – from slack key guitar to steel guitar to falsetto singing – as I can without stretching myself so thin that I break. I was raised on Territorial Airwaves, and Harry B. Soria is a friend without whose encouragement I would have stopped participating in – and would never have won – the Aloha Festivals Falsetto Contest which he hosted. But there are myriad ways in which Ho`olohe Hou is not a carbon copy of Territorial Airwaves. It is largely my approach to analyzing (or overanalyzing) Hawaiian music that ensures that Ho`olohe Hou is not Territorial Airwaves. I approached Ho`olohe Hou as if I had sold it to NPR. I was Sam the Eagle to Harry’s Fozzie Bear. Ho`olohe Hou may have even been a first in Hawaiian music broadcasting – “edutainment.” I wanted to have fun, but I felt it was my kuleana (or responsibility) to educate. On January 1, 2013, I returned to blogging in the name of Ho`olohe Hou – offering up rarities from my collection a few at a time along with the stories of the artists and composers and the details of how the music is actually made – nuggets of information which might otherwise be lost on non-musicians. Facebook – which did not exist when I began attempting to broadcast – made it easier to reach Hawaiian music lovers. But here is the rub. In the 20 months since its re-re-launch, with dozens and dozens of posts and episodes to its credit, Ho`olohe Hou has more than 400 Facebook followers and an amazing more than 10,000 downloads. Despite that the month is not yet over, there have already been more downloads in August 2014 – more than 1,000 – than in any other month in the program’s history. And yet I don’t know you. When Ho`olohe Hou was a radio show, I received more fan mail than I could respond to. But despite the instant communication that Facebook affords us, I have not heard from you. I realized this when a recent post about Kui Lee received more than 400 downloads but only a half dozen “likes” and only two comments. So in the tradition of my radio show, I have to ask… This is Ho`olohe Hou. Are you listening? If so, let me know. Write me at hwnmusiclives@gmail.com or comment on a post that moved you. Or recommend an artist, a composer, or a musical style to be profiled, and I would be happy to oblige. Meanwhile, I give you a Ho`olohe Hou anniversary gift – the entire two hour broadcast of the first episode of Ho`olohe Hou originally aired on August 19, 2007.* Check out the original playlist (at this link). What do you see? The show was chock full of rarities you would likely hear nowhere else. At the time, almost all of the recordings I was spinning were out of print (as indicated by the asterisk in the “LP/Source” column at the link above). I offered long forgotten rarities not available on CD or MP3 by Sonny Chillingworth, Alfred Apaka, Sterling Mossman, George Kainapau, Chick Floyd, Poncie Ponce, Karen Keawehawai`i, Kekua Fernandez, Marlene Sai, George Paoa, Ihilani Miller, Alice Namakelua, and Don Ho. Seven years later, all of those recordings remain out of print. More than this, who else would inform you that one of Sonny’s ethereally voiced back-up singers was none other than Nina Keali`iwahamana, that the ridiculously jazzy steel guitarist backing Poncie Ponce was California-based Vince Akina, or that the falsetto singing in George Paoa’s trio was Buddy Fo and The Invitations’ highest voice, Johnny Costello? Only a musician would know these things because there were no credits on the album covers. These are discoveries that can only be made with the ears. It is my fondest desire to put Ho`olohe Hou the radio program back on the airwaves. If you think you know someone who can help fulfill my dream once and for all, please reach out to me. Until then, Ho`olohe Hou will remain a blog which – in case you do not realize the intricacies of copyright law – is as illegal now as it was when I started on January 1, 2006. Despite that I make no money from this labor of love, despite the historically and culturally important service of preserving this music, artists and composers still demand to be paid. Fortunately, since its inception seven years ago (or nine years ago, depending on when you start counting), no artist has asked for compensation. Either they “get it” or Ho`olohe Hou remains unnoticed. I do not fancy myself either a pirate or a Robin Hood. With your help, maybe I will someday soon find the way to fulfill this mission legally and ethically Until then, as I said at the close of every episode of Ho`olohe Hou, “Keep aloha in your hearts, and take Hawaiian music wherever you go. A hui hou…” Me ka ha`aha`a – Bill Wynne

*Note that in order to listen continuously to this program, you will need to open a separate browser window. Closing that browser window will stop the streaming of the program. Note also that it may take up to 10 minutes to buffer the entire two-hour program.

|

Sun, 17 August 2014

George Paoa was born on August 17, 1934 in Honolulu. He got his start on a radio station KGMB contest program, the Listerine Toothpaste Amateur Hour, on which surprisingly he only took second place. But from this humble beginning Paoa went on to great renown performing with Kui Lee and with Johnny Spencer and His Kona Coasters both in Hawai`i and on the mainland in Reno, Tahoe, and Las Vegas. When he returned from the mainland, he performed with Don Ho at the original Honey’s Tavern in Kane`ohe. By 1966 Paoa had moved to Maui where he eventually performed at the Ka`anapali Beach Hotel, the Maui Hilton, the Royal Lahaina, and the Maui Prince. Finally, in the late 1990s, he moved to Lana`i where he held court nightly at the Lodge at Koele until his passing in 2000. Paoa was a percussionist and a pianist with a wonderful jazz sensibility in his playing. But, more than this, he was known for his beautiful and lush baritone voice. Although Paoa recorded at least a half dozen LPs throughout his lengthy career, as is often the case with Hawaiian music (and, in particular, the artists featured at Ho`olohe Hou) there remains only one George Paoa album in print in any medium in the digital era. On the occasion of George Paoa’s birthday, here are two cuts from two of Paoa’s finest albums that are no longer available. “There Goes Kealoha” – a once popular hapa-haole number written by Liko Johnston and Howard Zeugner, now seldom heard except when revived by the Brothers Cazimero (purely for its comic value, especially when accompanied by the hula of Leina`ala Heine Kalama) – is performed here by Paoa from his first solo LP, the 1960 Sounds of Hawaii release To Make You Love Me, Ku`uipo. “Hula Heaven” is from a 1970s live recording in which Hula Records captured George and his trio at the Maui Hilton. From this recording you can hear the influences of the jazz piano trio (such as those led by Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, or the one Tommy Flanagan led to back singer Ella Fitzgerald) on George’s style. The trio here is rounded out by two mainstays of the Hawaiian music scene, Lee Pacheco and Johnny Costello. Interestingly, however, we have no idea who is playing which instruments since everybody in the band could handle all of the instruments heard here. The high falsetto voice clearly belongs to Costello formerly of the vocal groups led by Richard Kauhi and Buddy Fo. And Lee Pacheco was also an accomplished songwriter who – under his pen name Leroy Melandre – wrote the still extremely popular “Malia, My Tita.” George Paoa passed away on a vacation cruise on April 24, 2000. I encourage you to learn more about this amazing musician by viewing a wonderful 20-minute interview with Paoa which has been graciously archived by `Ulu`ulu, the official Hawai`i state archive for moving images. |

Sat, 16 August 2014

Although she wrote very few songs, Ihilani Miller wrote intricate melodies with harmonic structures (i.e., the chords) that showed a sensibility for jazz and the American musical theater. This means that by their very nature, then, they were not easy songs to sing. They require (as they say in the singing business) “chops.” And perhaps this explains Auntie Ihilani’s advice to me: “Just sing the song.” For if the song is well written, then it should require no embellishment from the singer. The best known of Auntie Ihilani’s compositions is, of course, “Kuhio Beach.” Because of the unusual huge intervallic leaps in melody, the song long ago became a favorite of falsetto singers – most notably Sam Bernard whose signature song this became. But more recently Hoku Zuttermeister recorded the song for his first solo CD, `Aina Kupuna, and while it is only one man’s humble opinion, I think this is now the quintessential version of the song (and everybody else should just stop singing it). It has become among Hoku’s most requested numbers, and he follows Auntie Ihilani’s first tenet of vocal performance: He just sings the song. But his voice combined with Auntie Ihilani’s ethereal melody become a vocal tour de force. Auntie Ihilani recounted the story of composing “Kuhio Beach” time and again… She attended school with a young lady who would go on to become a Hawaiian music legend herself – her friend Linda Dela Cruz. On the bus on the way to school one day, Ihilani spied some beach boys and felt this song coming on. Linda said, “I guess we’re going to play hookey.” And although Ihilani shook her head “no,” when they got to their stop at McKinley High School, they stayed on the bus all the way to the end of the line. On the reverse trip, they passed the school yet again and got off at Ihilani’s house where she unabashedly explained to her mother that she couldn’t write music with school interfering. But there was too much noise at Ihilani’s house too. So they made for Linda’s house, and in the peace and quiet there, Ihilani banged out this classic in a half hour. Like “Kuhio Beach” before it, “Pakalana” has become another favorite among falsetto singers. In recent years Auntie Ihilani’s composition has received beautiful treatments from two Aloha Festivals Falsetto Contest winners – Kalei Bridges and Kalani Bernanua. But, as with Hoku Zuttermeister and “Kuhio Beach,” all others should stop singing “Pakalana” since none other than Raiatea Helm recorded it on her second solo CD, Sweet & Lovely. Raiatea sought out the assistance of Auntie Ihilani in order to ensure her performance was just right, and she enlisted an all-star supporting cast to assist in the recording: Bryan Tolentino on `ukulele, Casey Olsen on steel guitar, and (surprise!) Hoku Zuttermeister on bass. If “Kuhio Beach” and “Pakalana” have become staples of the Hawaiian music repertoire which continue to increase in popularity among younger performers, then the sleeper among Auntie Ihilani’s compositions remains “Nohelani.” As recounted in a previous post, the song was composed to honor the birth of a daughter to one of Auntie Ihilani’s dear friends and musical partners, Lei Cypriano (of the Halekulani Girls). The daughter in question, Nohelani Cypriano, went on to become a superstar of Hawaiian entertainment in the 1970s and 80s. Few have performed “Nohelani” besides Auntie Ihilani, and nobody has recorded the song since Ihilani herself on her one and only LP, Ihilani, Voice of the South Seas in the 1950s. Because Auntie Ihilani was a dear friend to me and had just passed away a few weeks before I was to perform at The Willows as part of the Pakele Live concert series, I chose to honor her by reviving this forgotten song which – selfishly – I feel is the most beautiful thing she wrote. And because by no means do I belong in a class with Hoku Zuttermesiter and Raiatea Helm as an artist, it is with great humility that I give you here my own version of “Nohelani” recorded July 10, 2011 at The Willows and performed with my longtime musical partners – Halehaku Seabury-Akaka on guitar, Ocean Kaowili, and Jeff Au Hoy on steel guitar. I hope you enjoy this tribute to one of my dearest friends and mentors. We miss you, Auntie Ihilani… - Bill Wynne |

Fri, 15 August 2014

Singer, dancer, choreographer, and composer Ihilani Miller was born August 15, 1932. With looks not unlike the Pacific version of Imogene Coca, Miller’s resume reads as impressively as any superstar of the pop or jazz world on the mainland in the 1950s. Miller performed all over the mainland – Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia – and was featured on the numerous TV talk and variety programs of the day hosted by Arthur Godfrey, Steve Allen, Mike Douglas, Alvino Rey, Ed Sullivan (of course!), Donald O’Connor, and even the Colgate Comedy Hour. But after living the life of a superstar for a while, Ihilani eventually settled down to a quieter life in Hawai`i – remaining active in the entertainment field later in life by continuing to perform many Friday afternoons as featured vocalist with the Royal Hawaiian Band in their performances at the bandstand at `Iolani Palace. While not a prolific composer, Auntie Ihilani wrote a few gems that have become oft performed classics. You no doubt know at least one. Who hasn’t heard “Kuhio Beach?” Kuhio Beach Where the moon shines on the sand And the beach boys are surfing in with the tide To the shore with girls side by side Regretably, Ihilani Miller only cut one LP in her lifetime – Ihilani. Voice of the South Pacific in the 1950s. There are very few copies floating around – even among collectors. But as I forged a friendship with Auntie Ihilani in her later life, I feel very fortunate to have received my copy of this gem straight from her hands and her heart. In this segment we hear two selections from that LP – one so haunting I dare you not to cry when you hear it. “Nohelani” is an original Miller composition written – in the Hawaiian tradition – to honor the birth of a child. Auntie Ihilani miller once performed in an “all girl” band led by singer/guitarist Lei Cypriano (later of the Halekulani Girls). “Nohelani” honors Lei’s daughter Nohelani Cypriano who went on to become a superstar of Hawaiian entertainment in the 1970s and 80s. If you are hearing Ihilani sing for the first time, you hear that her vocal style bridges a gap between opera, Broadway, and the pop stylings of, say, Eydie Gorme. She also has an incredible vocal range – allowing her to ring every last bit of emotion out of her composition. But it is the dynamics on the last note – the volume swell and subsequent decrescendo – that rip my heart out every time. “The Breeze and I” has origins in both Cuba and Spain. Originally an instrumental entitled “Andalucia” by Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona, a Spanish lyric was added later by Emilio de Torre, and finally later the English language lyric Auntie Ihilani sings here composed by Al Stillman. The orchestra of Jimmy Dorsey struck gold with the instrumental in the 1940s, and singer Caterina Valente took her vocal version all the way to #13 on the Billboard charts in 1955. This is approximately the same time period to which Auntie Ihilani’s LP dates, but as Ihilani, Voice of the South Seas was produced by a small local label – not one of the big corporate production houses that could have gained national distribution traction – despite that Ihilani’s version of the tune is far more compelling, it never had a chance. Ihilani Miller passed away on May 17, 2011. I still haven’t come to terms with this because we continued to grow closer near the end of her life. We met on September 11, 2004 when I was a contestant in the Aloha Festivals Falsetto Contest and she was a judge. This was the beginning of a beautiful, but too brief friendship. She gave me the most valuable singing advice anyone had given me before or since: “Just sing the song. Tell the story. If the song is well written, then you don’t need all of the vocal gymnastics these young people attempt today.” Despite that Auntie Ihilani made her home in Ewa Beach later in life, she was born and raised in Kapahulu and kept close ties to that side of the island. When last we spoke, she was planning a vacation – to spend two weeks in Waimanalo at the home of Auntie Nickie Hines. |

Wed, 13 August 2014

In 1983 Robert and Roland – known collectively as the Brothers Cazimero – released a forgotten classic of contemporary Hawaiian music. Among Cazimero releases, “Proud Family” was a bit of a “sleeper” which did not contribute all too many songs to their “Best Of” collections or frequent fan requests. (The LP is probably best remembered for the radio hit “Tropical Baby” and for their cover of Ken Makuakane’s “Maui On My Mind.”) What “Proud Family” did not feature was all too many of Robert and Roland’s more radical takes on a traditional Hawaiian song. Almost every Cazimero release up to this point had taken one or more staples of the Hawaiian canon in which the duo consciously infused their unusual (and still then considered unorthodox) influences from rock, jazz, or other musical idioms. But “Proud Family” was fairly straight-ahead Hawaiian music for its time – perhaps even (by Cazimero standards) a little behind its time. Robert and Roland chose not one, but two of Auntie Alice’s compositions for the sessions that led to “Proud Family” which are offered up in this segment of Ho`olohe Hou. One can only wonder if Robert and Roland were in the studio reflecting on Auntie Alice’s accusation that they were “bebopping the music” when they arranged the songs – one in a rather traditional mode (almost exactly as it was written) and one almost nothing like Auntie Alice composed it. Auntie Alice composed “Hanohano No `O Hawai`i” for the Hawai`i island float in the 1958 Kamehameha Day Parade. In her own words, “Now they all want me to ride float, so I will make a new song for it.” In this mele, she extols the beauty and pride of her home island. If there is anything unorthodox about the Cazimero recording of “Hanohano No `O Hawai`i,” it is not merely the use of the 9th chord throughout (instead of the expected major chord). It is more importantly and strikingly the end of each verse. Auntie Alice wrote something very typically Hawaiian at the end of each verse – a chord progression from secondary dominant to dominant to tonic (or V7/V-V7-I, or in the key of F, G7-C7-F). But Robert and Roland do something more rhythm-and-blues oriented with this section – a progression of Bb7-Ab6-F9. This is not unlike something you might hear Howling Wolf or Muddy Waters (or, later, Keith Richards) play. I have spent 30 years wondering what Auntie Alice thought about this. But something tells me that Robert and Roland know. Despite Auntie Alice’s private and public admonishment of the directions in which the young lads were taking Hawaiian music, the Brothers Cazimero continued to grind the past and the future against each other to find an acceptable evolutionary compromise. We understand now that this was their unique role in the history of Hawaiian music. The brothers take a far less confrontational approach to Auntie Alice’s “Aloha Ko`olau” which she composed while taking a drive with her nephew from Punalu`u down O`ahu’s windward coast. Parsing out the mele, students of the Hawaiian language might be quick to believe that the lyric is filled with the poetic technique known as kaona – or veiled meanings – and that this is not merely a song about a drive, but also a love song. But those who knew Auntie Alice have pointed out that she exclaimed repeatedly that her songs mean exactly what they say – that her compositions did not possess kaona unless she said they did. And perhaps her response in itself was the kaona since the true spirit of that art form dictates that only the composer will ever really know who and what the song are about… |

Tue, 12 August 2014

Alice Ku`uleialohapoina`ole Namakelua was born August 12, 1892. How do we come to grips with how long ago this really is? To give us some perspective, Alice was once a servant in the kitchen of Queen Lili`uokalani. But this is not what she is remembered for… Auntie Alice was many things to many people as she was in her time arguably the most important keeper of knowledge and understanding of the ways of a Hawai`i long forgotten by almost everybody else - because she was there. And she lived a purposeful life of sharing her history – Hawai`i’s history – with all of those who cared to listen and perpetuate. There are many “Alices” in Hawai`i’s history. But everybody knows who you mean when you say “Auntie Alice.” There was only one. And if you were a young musician in the 1960s or 70s, whether or not you were formally under her tutelage, you were scolded by her at least once. And this was, they say, the greatest lesson you could ever receive. Ask Robert and Roland Cazimero who have on many occasions lovingly recounted the hard lessons learned from being too cavalier or careless with their music – especially with the Hawaiian language – and being brought around to the light, to what is correct – or pono – by Auntie Alice. In addition to being such an invaluable resource, Auntie Alice was one of the most prolific composers in Hawai`i’s history, having written more than 170 songs. She was also a slack key guitarist – one of the first females to promote the art form and one of the few living direct descendants to the real old style that few Hawaiian slack key artists were playing in her time. Because of her, modern slack key practitioners such as Ozzie Kotani have learned this older, simpler style, documented it both in writing and with recordings, and have passed it along to present and future generations. All because of Auntie Alice. Aficionados of Hawaiian music and budding slack key guitarists should hear this style at least once, and they should hear it played by Auntie Alice. Despite composing so many tunes, she went into the studio only once in the mid-1970s by which time she was already 80 years old! On this recording cut for Hula Records, Auntie Alice sings her own compositions while accompanying herself with the slack key guitar in this oft forgotten style – making the album a gem, a must-have in any Hawaiian music collection. But, sadly, the recording has been out of print for nearly 30 years and is most elusive even to collectors. From this album you are now listening to Auntie Alice’s composition “Waipi`o Paka`alana.” Take note of the slack key guitar style which is played with only two fingers on the right hand – the thumb focused on a bass line (which outlines the chord that is not being played) and the pointer (or, alternately, the middle finger) which is playing a melody which becomes a de facto counterpoint to the melody she is singing. Notice that there are no strums and at no time does Auntie Alice play a full chord (which is typically defined by three notes). This is the simplicity of the old slack key guitar style. Auntie Alice passed away in 1987 at the age of 95, but not before leaving a legacy of Hawaiian music, hula (which we have not even discussed here), and history without which arguably Hawaiian culture would not be the same today. |

Tue, 5 August 2014

I have already described the relationship that Kui shared with Don Ho – best friends, a friendship rooted in mutual admiration and, perhaps, later a rivalry that propelled each of them to greater heights, achievements neither could have known without the other. A symbiotic relationship. But nowhere did this evidence itself more than in one of the rarest recordings from my collection. Don graduated from Honey’s Kane`ohe to Honey’s Waikiki (at Lili’uokalani and Kalakaua Avenue) to – finally – what was then one of the biggest showrooms in all of Hawai`i – Duke Kahanamoku’s which, in the early 1960s, opened in the location that was Don The Beachcomber in the International Marketplace. At this same time Kui was down the street in Kapahulu with his wife, Nani, headlining the Surf Lanai at the Queen’s Surf. Don’s star was shining ever brighter by performing a repertoire comprised largely of Kui’s compositions, while Kui – performing the same songs – was at the smaller, far more intimate room well off the Waikiki strip. But Kui held no grudges as we hear in this rare clip. He continued to write, and he continued to give Don his best material – which Don did not squander in his ascent to the worldwide fame that Kui would never know. Various sources credit Kui with writing his biggest hit – “I’ll Remember You” – in 1965, while others credit him with writing it in 1964. But in this clip, Kui himself states that he wrote the song “a year and five months ago.” And this recording dates to 1964 – early in Don’s tenure at Duke’s. We know this only because Kui – among his many comments – congratulates Don on having recently opened at Duke’s, which happened in 1964. So if “I’ll Remember You” was written “a year and five months” before Don opened at Duke’s, then the song dates back at least to 1963. We also have the even earlier recording of “I’ll Remember You” that Flip McDiarmid II captured at Honey’s Kane`ohe (later released as the LP titled “Waikiki Swings,” discussed here earlier). What does this mean? Not necessarily that the documentarians got it wrong, but that we should not confuse when a song gets published with when it was written. Many songs are written without ever being published. So what makes this clip so rare? Its origins are unknown. Don made many live recordings – at least three at Duke’s. But this is not one of them. By its sound quality we might assume that it was a bootleg – that someone was brazen enough to walk into Duke’s one evening with a portable tape recorder which, in that era, were open reel tapes, meaning that the machine could not have been fewer than 18 inches by 10 inches by 10 inches, an 1800 cubic inch monster of a box, difficult (if not impossible) to conceal. So it is likely not a bootleg. Perhaps this was a local telecast (as opposed to the national Don Ho TV specials sponsored by Singer Sewing Machines, most released later as LP records). And perhaps somebody captured it with the monster open reel tape recorder sitting next to their television speaker. Regardless of the dubious origins, the “taper” could not have known that they would capture pure magic – a rare moment regardless of the artist. And that is the debut of a brand new composition, sung by its composer. It is also rare because it is one of the few recorded examples we have of Kui speaking and – in this case – speaking from the heart, about his life, about his craft, and about his friend. And, finally, it is rare because it is possibly the only tape of Don and Kui singing together. In a somewhat roundabout poetic way, Kui talks about what it means to “remember” and the writing of “I’ll Remember You.” What he does not tell you is that he did not compose the song because he knew he was dying. (From the timeline above, you now know that the song was written long before Kui’s diagnosis.) Kui wrote “I’ll Remember You” for the first of many occasions when Auntie Frances – I’m sorry, I mean Nani – got disgusted with Kui and split – leaving Hawai`i and heading home to her sister, Libby, in New Jersey. Kui says “Why do I have to remember?” What he means is “Why did I give her so many reasons to go? I would not have to remember if she were still here.” And that is the genesis of the song that Kui and Don debut here – “She’s Gone Again,” written after Nani returned to Hawai`i, gave Kui another chance, and – ultimately – came back to New Jersey again. Nani was indeed gone – again. In writing “She’s Gone Again,” Kui used what is essentially the same harmonic structure (i.e., the chords) from “I’ll Remember You” but wrote a new melody to fit his new lyric. This means that the now classic interpolation (that is, the combining of two related songs) of “I’ll Remember You” and “She’s Gone Again” was indeed no accident. Kui wrote the two songs to be sung this way and debuted it this way, as you will hear. It has since become a classic duet – typically for a man and a woman – which Don reprised in his act over and over again, a staple of his repertoire. But what we didn’t know was that the first time the two songs were ever sung this way was by a two gentlemen – Don and Kui. And we know by Don’s patter here that they had just worked out the arrangement late the night before (possibly after the 3am set ended), early that morning (unlikely after being on stage until the wee small hours), or in the minutes right before the live show. There was not much to arrange except – as Don states here – the “turnaround,” and he apologizes in advance should The Aliis mess up that section. But they don’t, and what you have here is a magical moment when composer and singer debut a classic composition together. And I cannot recount any other song that has debuted so publicly by being sung jointly by the composer and the singer for which it was intended – not in Hawai`i, not in any other musical genre, not even Burt Bacharach and Dionne Warwick. Finally, the real tone of the friendship between Don and Kui may be revealed in this all too short clip. Kui speaks genuinely about how proud he is of Don – referring to Duke’s as a “gigantic room” and Don’s contract as a “major breakthrough” in an era when Waikiki was not host to “too many brown people.” After the debut of the new composition, Kui walks away most humbly – huge fanfare, without encore. And Don shouts after him, “You’ll be here one day.” He never was. Kui was gone only two years later. Next time: A few more Kui Lee compositions that helped but Don Ho and The Aliis on the map… ~ Bill Wynne |

Sun, 3 August 2014

Kui returned to Hawai`i in 1961 bringing him with great success and an even greater prize – a wife. He met singer and hula dancer Rose Frances Leinani Naone – a Hawaiian girl born in New Jersey – when she auditioned to perform in the famed Hawaiian Room of the Lexington Hotel in New York City where Kui spent the last year and a half of his mainland career as a choreographer and knife dancer. The couple was earning $1,700 a week when Kui decided to pack it in and go home. This dynamic duo would eventually find engagements across both O`ahu and Maui – eventually headlining the Queen’s Surf, selling it our night after night. But the couple started out much more modestly on their return – at a small mom-and-pop joint in the neighborhood they made their home, Kane`ohe. The place was called Honey’s. Should it matter that the club was owned by a family named Ho and that the house band was led by their then unknown son, Don? It turns out it matters a great deal. In fact, it is the very definition of “serendipity.” It would be an understatement to say that in the early running Kui made a nuisance of himself at Honey’s. According to Jerry Hopkins’ “Don Ho: My Music, My Life,” Kui would show up at the club at 10 o’clock in the morning when Don – being the owner’s son and not yet a “star” – was doing whatever family needed to do to make a bar and restaurant run. Kui would urge Don to hear a new song he had written, and Don would tell Kui that the songs – because of their complex melodies and harmonic structures – weren’t “Hawaiian” enough for Honey’s local audiences. And the criticism was mutual. Kui – no stranger to large mainland showrooms – would offer Don unsolicited advice on everything from lighting and staging to his singing, remarking, “When you sing, you look like you’re constipated.” It is difficult to conceive that a relationship born in perpetual appraisal and fault-finding would culminate in a lasting friendship and artistic collaboration that endured until Kui’s early demise. But both became huge stars through this no doubt symbiotic relationship. With this bickering, each propelled the other on to greater heights – each becoming a legend in his own right, but the whole always remaining greater than the sum of its parts. Don needed Kui’s songs to become legend. And Kui – despite being the consummate showman – needed Don’s charisma and universal appeal to bring his songs to a worldwide audience. Despite Don joking to Nani that he would hire her for the band but “definitely not your husband,” both became regulars in the Honey’s Kane`ohe group – a group that was the launching pad for countless other future stars of Hawai`i entertainment including songbird Marlene Sai, slack key guitarist Sonny Chillingworth, `ukulele virtuoso Tony Bee, bassist and romantic baritone Gary Aiko, singer and entertainer Zulu (who went on to his own stage show in Waikiki as well as starring in several seasons of the original “Hawaii Five-0” TV series), and singer Alvin Okami (who put his singing aspirations aside for 40 years to build first a successful plastics firm and then – today – KoAloha `Ukulele). (And, yes, Don really played the Hammond chord organ. It was not merely a prop.) There is little tape remaining from that era. But there is a particularly controversial one that lingers in the vaults of ardent Hawaiian music collectors. In 1962 – long before Don would become famous – Hula Records’ owner Donald “Flip” McDiarmid II heard about the magic that was happening in Kane`ohe every night at Honey’s. So he went over there one evening with a portable tape recorder and captured part of the magic of an evening at Honey’s exactly as it happened. The material recorded that evening was eventually released on the Hula Records label under the title “Waikiki Swings!” despite that the recording was of subpar sound quality. It sounded like what it was – a “bootleg.” I spoke to Flip in his home shortly before his passing in 2010, and this tape was one of the topics I broached. According to Flip, he had taken the recorder in to capture some of the magic so that he could review it to see if he had an album in the making in order to offer a deal to the participants in the band at Honey’s. If the deal had come to fruition, Flip would have returned with a professional remote recording crew and made an “album.” No such deal ever came to fruition. Don held out for a national deal – which came after his show moved to Duke Kahanamoku’s at the International Marketplace in Waikiki just a year or two later. However, according to others familiar with the situation, there was no such deal in the making; the recording was a bootleg – and pure and simple – and when Don released his first two live albums nationwide for Frank Sinatra’s Reprise Records label in 1965, Hula Records released the bootleg from Honey’s in 1966 to capitalize on Don’s burgeoning success. Making the accusation even worse, some involved with the performance captured that evening claim that they were never paid when “Waikiki Swings!” was released. I am not an investigative journalist. So I chalk up these conflicting tales to there always being “two sides to every story.” And if time has the capacity to heal many (surely not all) wounds, it may merely be because memory invariably fades and, with it, the scars. Regardless of McDiarmid’s motivations, nobody can deny that he captured an important moment in Hawaiian music history – a pre-fame Don Ho and possibly the only extant live recordings of Kui and Nani Lee. The selections offered here are those portions of the evening which featured Kui or Nani. (I could have posted the entire album since nearly every song sung that evening – including those performed by Don and Alvin – were Kui’s compositions.) But here I wanted you to have a taste of Kui and Nani the entertainers. Occasionally, Don would allow Kui to emcee the evenings at Honey’s, but he did so with great trepidation. Despite being first and foremost a musician, Kui was sharply funny – often turning his rapier wit on the audience, earning him the nickname “Hawai`i’s Lenny Bruce.” (In the Jerry Hopkins book on Ho’s life, comedian Eddie Sherman recounted that one evening at Honey’s in Kane`ohe, Kui spotted a haole couple at the front of the audience and quipped over the microphone that in Kane`ohe “the haoles sit at the back of the room.”) You will hear some of Kui’s political incorrectness on the first tune in this set – his own rewrite of the folk tune “Cotton Fields” which he recast for local audiences as “Taro Patch” – as well as near the end of the set, a duet with his wife, Nani, on Bina Mossman’s “He `Ono” during which Kui takes time out to provide some revisionist history of the "discovery" of Hawai`i and explain some of the ethnic make-up of Hawai`i (perhaps for the haoles at the back of the room). But there are tender moments here too. Many of Kui’s fans believe that many of his compositions take on their poignancy because he composed them after he was already diagnosed with cancer. He knew that his life was to be cut short, and this resulted in such lyrics as “If I Had It To Do All Over Again,” made popular by Don. But more poignant than this is hearing him sing his own “When It’s Time To Go.” When it’s time to go Will I be a bore And react, my friend Like a fool once more I listen to this song and can't help but highly suspect that this is one of those songs that Don would not have liked when Kui brought it to him - with its meandering jazz chord structure and an unexpected shift from major to minor and back again. Don told Kui, "Just play five simple chords and you'll be surprised how beautiful the song can be." And yet I cannot imagine a more beautiful song in any genre from any land. And Nani sings her husband’s “Where Is My Love Tonight?’ like the seasoned pro she was – a vocal performance that would have stood comparison to such jazz chanteuses of the era as Nancy Wilson, Nina Simone, and Morgana King. I hope you enjoy these sounds of a forgotten era – a simpler time when fun was cleaner and the consequences less dire – as well as this rare glimpse of the equally magnetic personalities that were Mr. and Mrs. Kui Lee. ~ Bill Wynne |

Sat, 2 August 2014